One of the best ways to familiarize yourself with a culture is to learn its national anthem. In Israel’s case, the anthem is called התקווה (Ha-Tikvah), which means “The Hope.” Not only will this earn you some street cred next time you’re at a sporting event in Tel Aviv or celebrating יום העצמאות (Yom ha-’Atzma’ut) in Jerusalem, it is a wonderful lens through which to examine modern Israel’s history and dig deep into issues of identity, politics, and ethnolinguistics.

In today’s fascinating lesson, we’re going to take you on a journey through the rise and development of Zionism as a movement, the adoption of Ha-Tikvah as the unofficial hymn of the nascent nation project that was eventually to become the State of Israel, and much more along the way. We’ll talk about the key figures involved in its composition and adoption and, of course, take a look at the actual lyrics and their meaning, both semantically and culturally.

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

- Lyrics to Ha-Tikvah, the Israeli National Anthem

- Ha-Tikvah’s Beginnings

- The Language of Ha-Tikvah

- Competition and Controversy Surrounding Ha-Tikvah

- How Ha-Tikvah Came to Be Adopted as Israel’s De Facto National Anthem

- When Is Ha-Tikvah Sung?

- Interesting Trivia about Ha-Tikvah

- We at HebrewPod101 Hope You Enjoyed Today’s Lesson!

1. Lyrics to Ha-Tikvah, the Israeli National Anthem

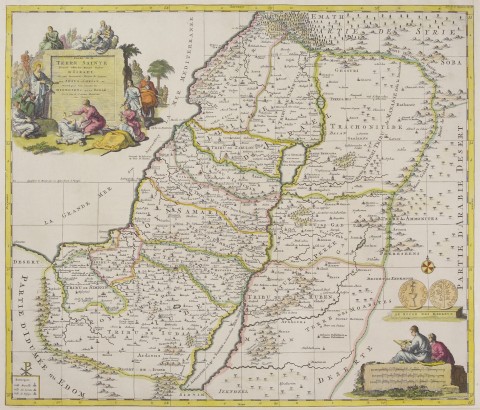

First things first! Let’s have a look at the lyrics of Israel’s national anthem, along with transliteration and translation. It is worth noting that the lyrics are part of a longer poem entitled תקוותנו (Tikvateinu), or “Our Hope,” written by the Galician Jew Naftali Herz Imber in response to the establishment of פתח תקווה (Petakh Tikvah, literally “The Gateway to Hope”), the first modern Jewish agricultural settlement in the Holy Land.

Herz Imber originally wrote his nine-stanza poem around 1878, though it was not published until 1886, when it was included in a compilation of Imber Herz’s poems titled ברקאי (Barkai, “Morning Star”) printed in Jerusalem. (Herz Imber had emigrated to Israel in 1882). The poem went through various iterations as it was circulated throughout different communities in the ארץ ישראל (Eretz Yisra’eil). It was ultimately truncated to its first two stanzas, which were set to music by Romanian immigrant to Israel Shmuel Cohen. You can hear the anthem sung below while you look over the lyrics.

| עברית (‘Ivrit, “Hebrew”) | Transliteration | English |

| כל עוד בלבב פנימה נפש יהודי הומייה ולפאתי מזרח קדימה עין לציון צופיה. עוד לא אבדה תקוותינו התקווה בת שנות אלפיים להיות עם חופשי בארצנו ארץ ציון וירושלים | Kol od ba’levav penima Nefesh yehudi homiyah U’lefa’atei mizrakh kadimah ‘Ayin le-Tziyyon tzofiyah ‘Od lo avda tikvateinu Ha-tikvah bat shenot alpayim Lihyot ‘am khofshi be-artzenu Eretz Tziyyon ve-Yerushalayim | As long as within our hearts The Jewish soul sings As long as forward to the East To Zion, looks the eye Our hope is not yet lost It is two thousand years old To be a free people in our land The land of Zion and Jerusalem |

2. Ha-Tikvah’s Beginnings

As mentioned, the original poem from which Ha-Tikvah emerged was penned by Naftali Herz Imber. Herz Imber started writing poetry at a young age, even winning an award for one from Emperor Franz Josef. An adventurous youth, he set forth from his native Galicia, then under the Austro-Hungarian Empire (and now a part of Ukraine), at age 19, traveling across Europe and the Middle East.

In Turkey, Imber Herz fatefully encountered Sir Laurence Oliphant, a British Member of Parliament who was an ardent supporter of the Zionist movement’s aim to resettle Jews in the Holy Land. Imber Herz accompanied Oliphant and his family to the Holy Land in 1882, living with him in Haifa and the Druze village of Daliyat al-Carmel. Oliphant sent Imber Herz to train as a watchmaker in Beirut, Lebanon, subsequently helping him to open a watch shop in Haifa, but Herz Imber was apparently not one to settle.

He moved to Jerusalem in 1884, where, as mentioned, he published his first collection of poems. This publication gave his poem Tikvateinu wide circulation, as did Imber Herz’s own readings when he visited settlements throughout the Holy Land.

3. The Language of Ha-Tikvah

While you may certainly learn or even recognize some words from the lyrics of Ha-Tikvah, it is important to note that its composition predates the true revival of Modern Hebrew as a spoken language. In fact, the first organization dedicated to promoting the use of Hebrew as a lingua franca in the Holy Land, the שפה ברורה (Safah Berurah, “Clear Language”) society, was not founded until 1889, three years subsequent to Tikvateinu’s publication and over a decade after it was originally written.

For this reason, the language employed in the poem from which the anthem’s lyrics are derived is fairly archaic. In fact, most of it is Biblical. Beyond simply emulating the Bible’s style, the original poem actually made numerous references to Biblical passages on themes like hope, salvation, and God. However, revisions and emendations through the years removed most of these, following a secularizing trend that aligned the text with Zionism’s largely secular character.

4. Competition and Controversy Surrounding Ha-Tikvah

It is worth mentioning that Ha-Tikvah was not the only text vying for the status of national anthem in Israel’s pre-state years. Apart from Psalm 126, there were some dozen texts in competition as a national anthem for a state still in the making.

Another poem of Imber Herz’s was even among the contenders, as was Chaim Nachman Bialik’s תחזקנה (Tekhezaknah, “Be Strengthened”). Israeli newspapers even weighed in on the respective merits of the two poems! Bialik’s song was widely used as the hymn of Labor Zionism. The marchlike character of the latter, though invigorating in a vein reminiscent of Communist revolutionary hymns, ultimately could not overtake Ha-Tikvah’s emotional impact.

Apart from mere competition, Ha-Tikvah had real detractors. As mentioned previously, the Biblical and specifically religious tone of the original poem did not strike a harmonious chord with Israel’s secular founders. On the opposite side of the spectrum, many religious Zionists felt that only a text taken from the Bible itself was worthy of serving as a national anthem to the fledgling state. Furthermore, the overt Jewishness of Imber Herz’s text found opponents among the hard left, as well as Israel’s non-Jewish communities, such as Muslim and Christian Arabs. Indeed, as late as 1967 (following the Six Day War), leftist Member of Knesset Uri Avnery introduced a bill to replace Ha-Tikvah with Naomi Shemer’s ירושלים של זהב (Yerushalayim shel Zahav, “Jerusalem of Gold”), though the bill never even made it to a vote.

Lastly, in terms of the music itself, Ha-Tikvah saw push back on a number of levels. Firstly, some objected that its music was neither original nor Jewish. The opening melody of the anthem, in fact, is almost identical to Czech composer Bedřich Smetana’s movement Vltava or Die Moldau from his tone poem Má Vlast.

It is, of course, entirely possible that rather than representing piracy, Shmuel Cohen’s tune simply may share a common Central European source with Smetana’s, a phenomenon ethnomusicologists sometimes referred to as a “tune family.” Along these lines, Israel’s first preeminent musicologist, Abraham Zvi Idelsohn, considered the tune to be an ancient “wandering tune” that he identified in various songs from places as far flung as Basque, Poland, and England.

Beyond arguments over Ha-Tikvah’s originality, there were also those who objected the mere fact that the text had been set in a minor key. Such objections seemed to center around the notion that a national anthem, in particular that of a country as hard fought for as Israel, should be uplifting and inspirational rather than gloomy or pained.

5. How Ha-Tikvah Came to Be Adopted as Israel’s De Facto National Anthem

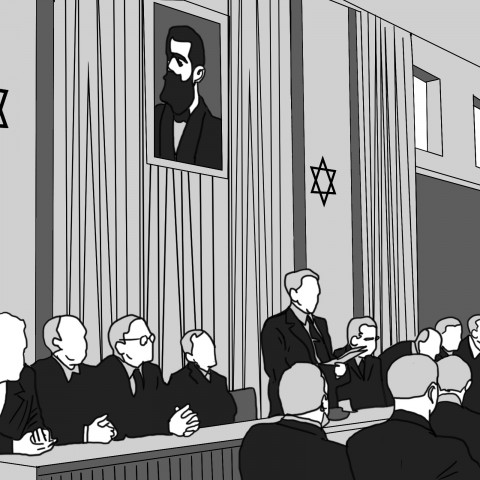

Amazingly, Ha-Tikvah was not officially recognized as the anthem of the State of Israel until 2004, though perhaps this is no great surprise coming from a country still without any written constitution. However, Ha-Tikvah has been sung as a Zionist national hymn at least from the Fifth Zionist Congress held in Basel, Switzerland, in 1901. It was subsequently sung at the Sixth Zionist Congress two years later, when, with its clear celebration of Jews’ ties to Israel and Jerusalem specifically, it made the perfect reply of rejection to the British offer of Uganda as an alternative national homeland for the Jewish people.

By the Seventh Zionist Congress of 1905, it was confirmed as the unofficial national anthem of the worldwide Zionist movement. It was sung at every subsequent Zionist Congress, as well as at other Zionist functions and functions gatherings across the globe. However, the song did not attain official recognition by the Congress until the 18th Zionist Congress, which also adopted the blue and white banner we know today as Israel’s flag. It was famously sung years later, when statehood was finally declared on May 13, 1948.

The song continually gained popularity, solidifying its singular status as the Zionist rallying song throughout pre-state Israel and the Diaspora in particular during the interwar years. Beyond the beauty of its lyrics, one might attribute this to the sense of solidarity it expresses, linking world Jewry by their ties, however far removed, to a common place and history – and today, to a common present and future.

6. When Is Ha-Tikvah Sung?

Ha-Tikvah may be sung at just about any official occasion, such as national holidays, political events, memorial services, graduation ceremonies, and even sports events – much like The Star Spangled Banner. It is not typically sung as part of synagogue prayer services, though it is played at the beginning of classical concerts and other cultural events. Outside, Ha-Tikvah is commonly sung at Zionist events, its lyrics representing so powerfully the eternal connection of Jews the world over to the Land of Israel and its capital, Jerusalem.

7. Interesting Trivia about Ha-Tikvah

Now that you know all the history surrounding Ha-Tikvah (and, of course, all the words by heart), let’s end on a fun note by taking a look at some trivia related to Israel’s national anthem.

- Naftali Herz Imber, like so many other luminaries in history, ended up in abject poverty. Having left the Holy Land in 1889 following a dispute with Sir Oliphant, he stayed for periods in England, France, Germany, and even India before arriving in the United States. Never able to achieve stability, Imber Herz died broke in New York City, in 1909, from complications arising from chronic alcoholism. Though buried in Queens, he was ultimately reinterred in Jerusalem in 1953.

- Some historians credit not Shmuel Cohen but Nissan Belzer with penning the melody for Ha-Tikvah. Then again, as mentioned, many highly similar melodies can be found throughout Europe. Some key examples are the 17th century Italian folksong La Mantovana by Giovanni Del Biado and the Sephardi prayer תפילת טל (Tefillat Tal, “Prayer for Dew”). In any case, Cohen never received a shekel of royalties!

- The British Mandate government banned the singing of Ha-Tikvah in 1919 in the wake of Arab anti-Zionist riots.

- Ha-Tikvah was so meaningful to Jews prior to the establishment of the State of Israel that it was sung on numerous occasions by Holocaust inmates even as they marched to the gas chambers. It was also sung in celebration at the liberation of camps like Bergen-Belsen, a song of an eternal dream that did not die even when so many of its dreamers had. You can hear a recording of the latter example here.

- A 2012 Peace Index poll conducted by Tel Aviv University found that 90% of Israel’s Arab citizens consider Ha-Tikvah “unsuitable” as a national anthem.

- Some synagogues conclude their יום כיפור (Yom Kippur, “Day of Atonement”) services with Ha-Tikvah. Additionally, some Jews include it at the conclusion of the סדר פסח (Seider Pesach, “Passover Seder”).

8. We at HebrewPod101 Hope You Enjoyed Today’s Lesson!

That’s all for today’s lesson. We surely hope you found it informative and interesting. And even if you already knew something about Ha-Tikvah, we’re betting you found at least one or two new facts to take away with you. More than anything, it is our wish that you find our resources useful and enriching, which is why we make sure to mix cultural and historical lessons with our grammar and vocabulary lessons.

Was there anything else you wanted to know about Ha-Tikvah or any of its related history? Would you like a lesson on some other Israeli song or any other aspect of Israeli culture? Let us know! We love hearing from our learners, and we always strive to ensure you stay interested, because an interested student is a motivated one! Reach out today. We’d love to hear from you! Until next time, shalom!